Background

The First Arrivals to Little America

On April 28, 1946, a small group of 379 wives and children disembarked from the U.S. Army transport ship Thomas H. Barry onto Columbus Quay at the port of Bremerhaven, West Germany. Among the mix of passengers, which included families of all ranks, were Mrs. Lucius D. Clay, Mrs. Mark W. Clark and the wives of 12 other generals. As an Army band played "The Stars and Stripes Forever" these military family members were ushered onto buses and trains that would eventually bring them to reunions with fathers, husbands, and fiances serving in the post-war American occupation force of western Germany. News accounts of the day noted that although soldiers at pier-side hailed them with remarks such as "You'll be sorry!" the new arrivals, flushed with excitement, chortled back, "No we won't."1 The following months and years witnessed thousands more family members (dependents) making the same trans-Atlantic journey. Their presence served as seeds for a network of military communities (Milcoms), often referred to as "Little Americas,"2 that would spread across the post-war West German landscape. (See Chart #1 on Milcom Demographics.)

Soft Power Conduits

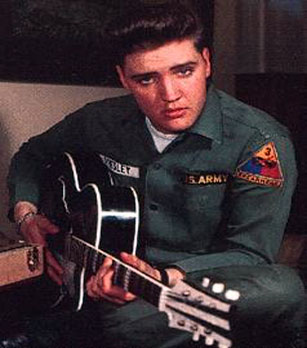

Along with ideological, political, and economic influence, the American presence also had a cultural impact on German society. Image Source: Wiki Commons.

American authorities were quick to realize that the establishment of the Milcom system was a palliative to calm the ill-disciplined urges of the U.S. occupation troops. The presence of families successfully reduced the high rates of crime and black market activites, widespread venereal disease, and fraternization. More important, after the successful relief by air bridge of Berlin in 1948, political and military leaders understood the benefit of these Milcoms as conduits of "soft power." 3 The presence of the "Little Americas" would serve as a grass-roots vehicle, both through example and people-to-people interaction, to convey the tenets of American Exceptionalism to the West Germans.

Project Scope

This project investigates changes to the American Exceptionalist consensus during the Cold War, 1950-1990 through the lens of overseas military communities. Focusing on Germany, it examines how those traditional traits of Americanism which included anti-socialism, anti-communism, anti-statism, class mobility, meritocracy, individualism, access to education, religion, and populism were central to post-1945 propaganda. These tenets were exhibited by the early Milcom residents who carried them abroad wrapped in an air of post-war triumphalism. More important, they were prescribed by elites in Washington who saw their exhibition as essential ammunition in the post-war ideological battle with the Soviets. Central to this project is an understanding that the consensus transformed over time reflecting contemporary social, political, cultural, and economic changes in the United States as well as around the globe. Included in this is a consideration of how America's evolving relationship with the Federal Republic of Germany informed revisions to the definition of American Exceptionalism.

Within the project scope there also exists an opportunity to examine the post-war German-American relationship through the lens of an inter-cultural borderlands study. It encourages a rethinking of American national history by understanding it as part of a broader transnational experience. As historian Mae M. Ngai notes, "transnational history rethinks not just national history but also challenges nationalist history."4

Internal Challenges to the Exceptionalist Consensus

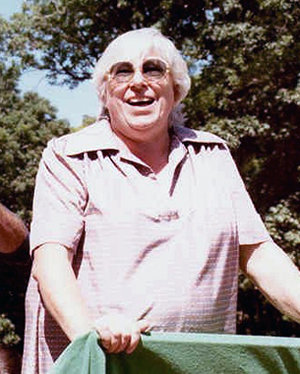

American atheists like Madalyn Murray O'Hair challenged the centrality of religion within the Exceptionalist consensus. Image: Wiki Commons.

Essential to this project is the understanding that the American Exceptionalist consensus was anything but immutable. There existed contested grounds where Milcom members applied different, and sometimes contradictory, paradigms derived from separate societal consensuses to interpret those American ideals. Among the most controversial were religion and race. These differences were fault lines in a seemingly solid exceptionalist consensus that under external forces would later widen and precipitate shifts in beliefs. Consideration of these types of inherent flaws is central to the project.

External Challenges to the Exceptionalist Consensus

Also central to the development of the project is an understanding that during the post-war period there were external dynamics that challenged the American Exceptionalist consensus. These began in the early 1950s with the emergence of the West German Federal Republic, which required a renegotiation of the German-American political power relationship. In parallel, there were economic challenges driven by the West German Wirtschaftwunder [economic miracle] and later, challenges from an expanding global economy, a weakening dollar, and a world-wide fuel crisis. Contributing to the assault on American Exceptionalism was the myriad of global cultural and social changes of the 1960s and 1970s, including energies from gender and race initiatives, and the unpopular war in Vietnam. This project will use the lens of the Milcoms to identify and track the influence of these dynamics on the Exceptionalist consensus.

Impact of the Media

The US government produced over 700 propaganda films for the "Big Picture" series. They focused on the ideals of American Exceptionalism and were aired to service members and their families during the post-war years. An example is shown below. Logo Source: Wiki Commons. Video Source: National Archives.

The study of certain elements of post-war print and visual media will take place as part of this project. Examining the manner in which the media informed and shaped opinions of Milcom members and in turn was edited and controlled by the political and military hierarchy for propaganda purposes, is part of the project methodology. This will include examination of print sources popular with the post-war Milcoms, such as the Stars and Stripes newspaper, as well as the Armed Forces Radio and Television Service (AFRTS) and scripted films prepared by US government agencies, which were all used to broadcast the tenets of American Exceptionalism. Consideration of congressional investigations into accusations of censorship and manipulation by military elites is also within this context.

Sources and Methodology

The Stars and Stripes was a principal news source for Milcom members, and reflected their views of the world. Image Source: Wiki Commons.

This dissertation will unfold as a grass-roots study of the network of Milcoms located in post-war West Germany during the period 1950-1990. The approach will follow cultural, social, economic, and political thematic lines. In this context it is essential to discover and mine those resources which establish the Milcom as a unique community shaped by directed and perceived understandings of American Exceptionalism and possessing its own values and identity. Together with a plethora of secondary sources that must bear examination and interpretation, there are important primary sources. These reside in archives located in the United States as well as Germany. In the United States they include the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, the Library of Congress, the US Army Military History Institute (USAMHI) at Carlisle Barracks, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In Germany they include the Military History Office of the US Army Headquarters, Heidelberg, and the Allierten Museum [Allied Museum] in Berlin.

Another aspect of this project's methodology is consideration for collecting oral histories from German and American sources. These can provide meaningful insight to understanding the American Exceptionalist attitude. A number of relevant collections exist at Rutgers University, the Virginia Military Institute, and the USAMHI. As historian Robert Grathwol observes, "One can enrich and expand the documentary record by using interviews with the Germans and Americans who had daily contact with one another in the garrison towns and hamlets of West Germany."5

Purpose and Impact

The purpose of this project is to investigate the reflection of the American Exceptionalist consensus in the Milcoms located in western Germany during the Cold War. Central to this is the goal of discovering how that narrative changed over time influenced by the tensions generated from contemporary cultural, social, economic, and political discourses. This includes developing an understanding of how the Milcom members acted as both subjects and agents, living within the constructs of the command-directed exceptionalist paradigm, interpreting its effects on their lives, and within their own limited agency reacting to and influencing change to that consensus.

The project will offer a fresh vantage point from the Milcom grass-roots perspective to study contemporary post-war history. In this context it will offer a lens to examine in greater detail the inter-cultural penetration that shaped American relations with Germany and influenced understandings of a broader trans-Atlantic economic, political, and cultural community. In parallel, it will also contribute to a historiographic process that considers U.S. history in a transnational global perspective.

American military families in West Germany represented a significant portion of such communities worldwide during the Cold War, and their counterparts continue to live at the borders between American and host-nation cultures in present-day occupation zones. This project will therefore provide interpretations that can contribute to a better understanding of the impact of these existing American Milcoms on other nations around the globe. That same approach can offer findings and conclusions that provide opportunities for former Milcom members to interpret, and make sense of, their past experience.